Farewell to the Hudson’s Bay Company

It has come time to say goodbye to the oldest joint-stock merchandise company in the English-speaking world. As of today, all of the Hudson’s Bay Company retail stores have closed their doors — forever.

I’m sad it’s come to this. I keep telling myself that the demise of a department store should probably be the least of my concerns in light of everything that’s going on in the world right now. But Canadians are feeling bruised, battered, and betrayed by the current American administration. Given the sense of patriotism and nationalism that is rising up in this country, at this moment in time, the loss of The Bay hits hard. The company holds a claim on Canada’s origin story in a way no other Canadian corporation does.

The Hudson’s Bay Company came into being on May 2, 1670, when King Charles II gave a Royal Charter to the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England Trading into Hudson’s Bay. It was set up as a commercial enterprise, but the company became the de facto government in many parts of Western Canada. James Douglas, first governor of the colonies of British Columbia and Vancouver Island, was also Chief Factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Most cities in Western Canada started out as HBC trading posts. I have vivid memories of school trips to Fort Edmonton Park with its full-sized replica of the HBC fort established on the banks of the North Saskatchewan River in 1795. The origin of the Métis Nation, one of three Indigenous peoples given legal recognition by Canada’s Constitution, is closely tied to the fur trade. Some of the first treaties with Indigenous peoples were signed by employees of the Hudson’s Bay Company.

The HBC coat of arms consists of two elks supporting a shield with a red cross and a beaver in each quarter. Above the shield sits a fox. The motto is Pro pelle cutem, which is Latin for “a pelt for a skin.” The beaver is now Canada’s national animal. The iconic point blanket, introduced in 1779, is called that because of its points — short black lines woven into the edge of the blanket just above the coloured stripes. The number of points indicates the size of the blanket.

A replica of an HBC trading post at the Glenbow in Calgary

After Confederation, the Canadian government negotiated with the Hudson’s Bay Company to purchase the vast land mass draining into Hudson’s Bay. Known as Rupert’s Land, it covered about a third of present-day Canada — what is now Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta, southern Nunavut and the northern parts of Ontario and Quebec. The company received payment as well as title to a portion of the land, including its trading posts. As such, Hudson’s Bay became a land developer in addition to being a fur trader.

The trade in furs lasted until 1987 when the northern trading posts were sold or closed. But over time, as the west was populated with European settlers, the company’s focus shifted from trading for furs to supplying settlers with the goods and tools they needed to homestead. It restructured itself into three divisions — land sales, fur trade, and retail — and opened the first of six stores in Calgary in 1913. Edmonton, Saskatoon, Vancouver, Victoria, and Winnipeg soon followed; the original six stores all have similar architecture.

The Hudson’s Bay store in downtown Vancouver was built in 1914.

The company didn’t expand into eastern Canada until 1960, when it purchased Henry Morgan & Company, a Montreal-based department store chain. In 1970, a new Royal Charter, granted by Queen Elizabeth II, formally transferred the company’s headquarters from London to Winnipeg. The headquarters moved again in 1974, this time to Toronto, the same year Hudson’s Bay opened its first Toronto store at Yonge and Bloor. This was a store I knew well, as I worked across the street for a couple of years and would often pop over to The Bay on my lunch breaks.

Hudson’s Bay continued to expand, swallowing up Simpsons, Woodward’s, and K-Mart. In 2005, it partnered with the Canadian Olympic Committee and became the official merchandiser for the 2010 and 2012 Olympics. Those iconic red mittens that were sold out everywhere? I grabbed a pair as a last-minute impulse purchase, months before the Vancouver 2010 Olympics, with no inkling they would become such a hot commodity.

Wal-Mart began operations in Canada in the mid-1990s, around the same time that online shopping became a thing. The business model that had sustained the Hudson’s Bay throughout the twentieth century began to shift. In 2006, the company was sold to an American businessman and then, two years later, to an American equity company. There was a brief foray into Europe — I happened to be in Amsterdam the day that store open. Talk about worlds colliding.

The Bay began its long slow decline over the last six years or so. Many blame its demise on the failure of its American owners to understand the Canadian marketplace. In 2019, it sold off 400 stores and closed the Home Outfitter stores it had been operating for 20 years. When the company applied for creditor protection two months ago, it had just 80 retail stores left, along with its online store.

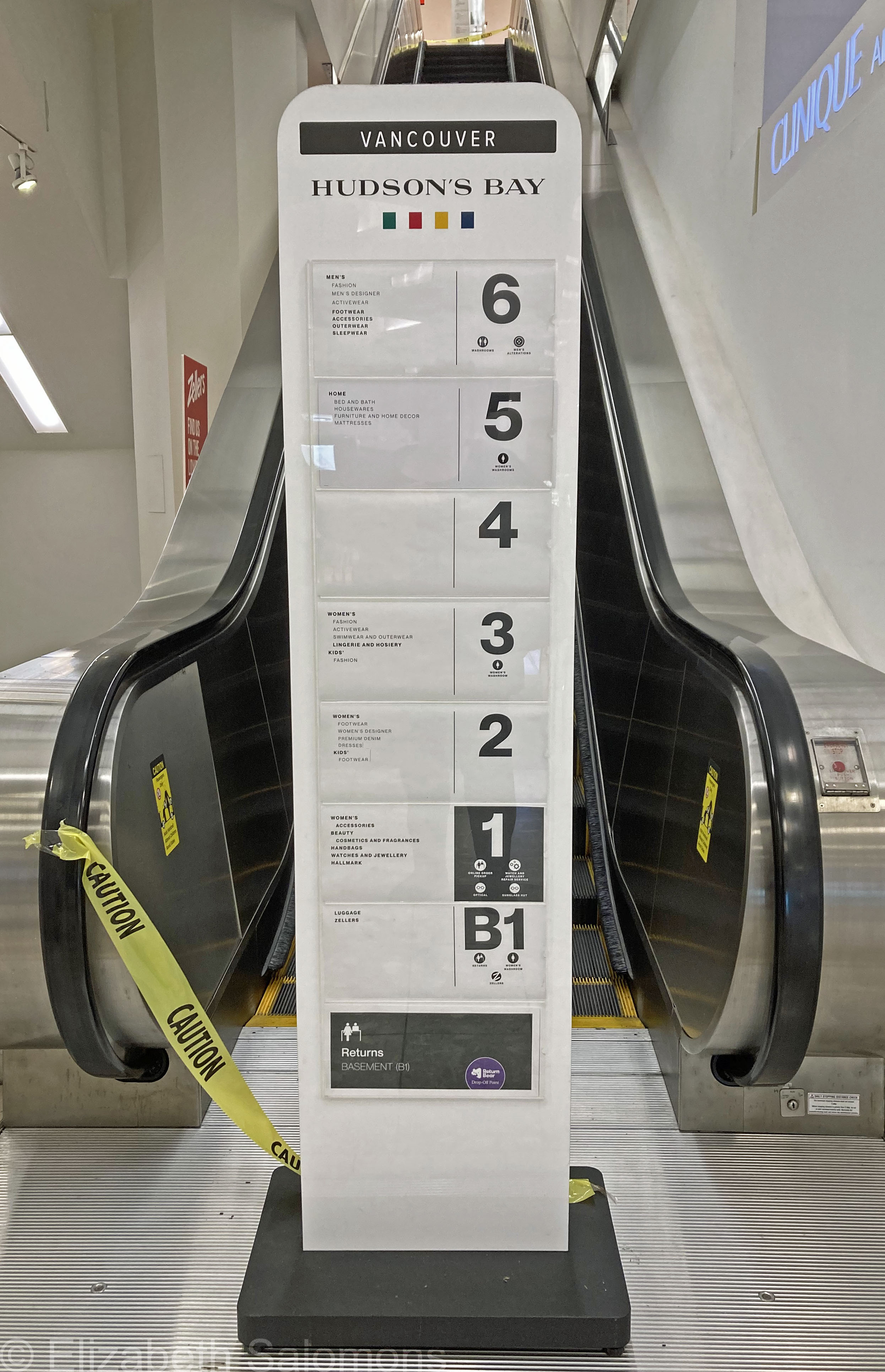

I have shopped at The Bay my entire life. Much of my kitchen was stocked at The Bay. It’s my go-to store for linens and socks and a fair-sized chunk of my office wardrobe. I even had a chance encounter with John Bishop, chef and former owner of Bishop’s Restaurant, in the housewares department while I deliberated over a choice of paring knives. But since the pandemic, I have struggled to find the items I want. When the elevators at the downtown Vancouver store were put out of service because the company couldn’t afford to maintain them, it was clear that Hudson’s Bay was on a downward trend that seemed unstoppable.

And so, while everyone was shocked, no one was surprised when the company went into receivership last March. I popped in to the downtown store on my way home from work shortly afterwards, looking for a point blanket. They had sold their last one just that morning, but I managed to snag the last cotton throw in stock. It has the signature stripes I was looking for.

I surprised myself when I choked up talking to the cashier who took my payment. He had only recently started working there, but said he felt bad for the women who had been working there for some 20 years. More than 8000 employees are out of a job as of today. In an economic climate that’s as unstable as Irish weather at the moment, I also feel for them.

With no working elevators, the stairs were the only way to the top in the Hudson’s Bay store in downtown Vancouver.

There is lots to still sort out. The HBC archives, consisting of thousands of business documents, personal journals, photographs, maps, artwork, and artifacts, are held in the Archives of Manitoba. But the company still has ownership of the Royal Charter, the one signed in 1670. Although it is a corporate document, it created a colonial government and is one of a handful of fundamental documents in Canada’s history, along with the British North American Act of 1867 and the Proclamation of the Constitution Act of 1982. Some have compared its significance to that of the American Declaration of Independence. It’s being auctioned off, will likely fetch millions, but I, like most historians, know it belongs in the archives, not a private collection.

I’m big on historical artifacts. I had always meant to get myself a point blanket and was kicking myself for having missed my chance. When my sister learned this, she offered me hers, which was sitting in a closet, unused. That blanket now sits in pride of place at the foot of my bed.

The role of the Hudson’s Bay Company in colonizing Western Canada is a complicated history that goes back 355 years and a month less a day. But, as I have written before, it is our history. And while department stores may not be the way we shop in this century, we can celebrate the history of the one where Canadians shopped for the past three and a half.