Happy Birthday, Jane Austen!

I wasn’t planning to write about the semiquincentennial of the birth of Jane Austen, born on this day in 1775. After all, I’d already written a post on the bicentennial of her death some years ago.

But when I woke up this morning, I thought, “C’mon. It’s Jane Austen! You need to post something.”

However, I’m a bit low on photos that represent Jane. The only place I’ve been to that connects with her life is Bath — and she didn’t much care for Bath. I was planning to visit Winchester, where she died and was buried, and where the house she lived the last eight years of her life has been turned into a museum.

In fact, I left Bath fully intending to go directly to Winchester. But after changing trains in Southampton, and realizing the train I had boarded was continuing on to London after it stopped in Winchester, I changed my mind. (You can do things like that with a BritRail Pass. I have to say: it’s very freeing, travelling that way.)

And so, I ended up in London that night. Winchester — and Jane Austen — would have to wait.

I always say, when travelling, that you should leave something undone to make sure you come back. One of these days (years?), I will return to Jane Austen country.

In the meantime, in honour of Jane Austen’s 250th birthday, here’s a photo of the Roman baths in Bath. I like the idea that Jane and I have both been to these baths — even though I missed her by almost 200 years.

Views of the Acropolis

The first thing I noticed while in Athens is how you see the Acropolis rising above the city every time you turn around. (It made me think of Paris, where you see the Eiffel Tower every time you turn around.)

Here are a few of the views I captured.

From the breakfast room at my hotel

From the top floor of the Maria Callas Museum

From the Acropolis Museum

From the Pnyx

From Plateia Jacqueline de Romilly (while enjoying

an Aperol spritz and some dolmadakia)

Through My Lens: Sea Squill on Serifos

One advantage of travelling solo, I (re)discovered this past fall, is that nobody gets impatient when you stop to take yet another photo. It took me several tries to get a shot I was happy with of this plant, which I came across one day while wandering the hillsides of Serifos, a Cycladic island in the Aegean Sea. (I’ve since learned that the plant is called a sea squill.)

I have lots more photos to share from my month in the Mediterranean.

Let’s get started.

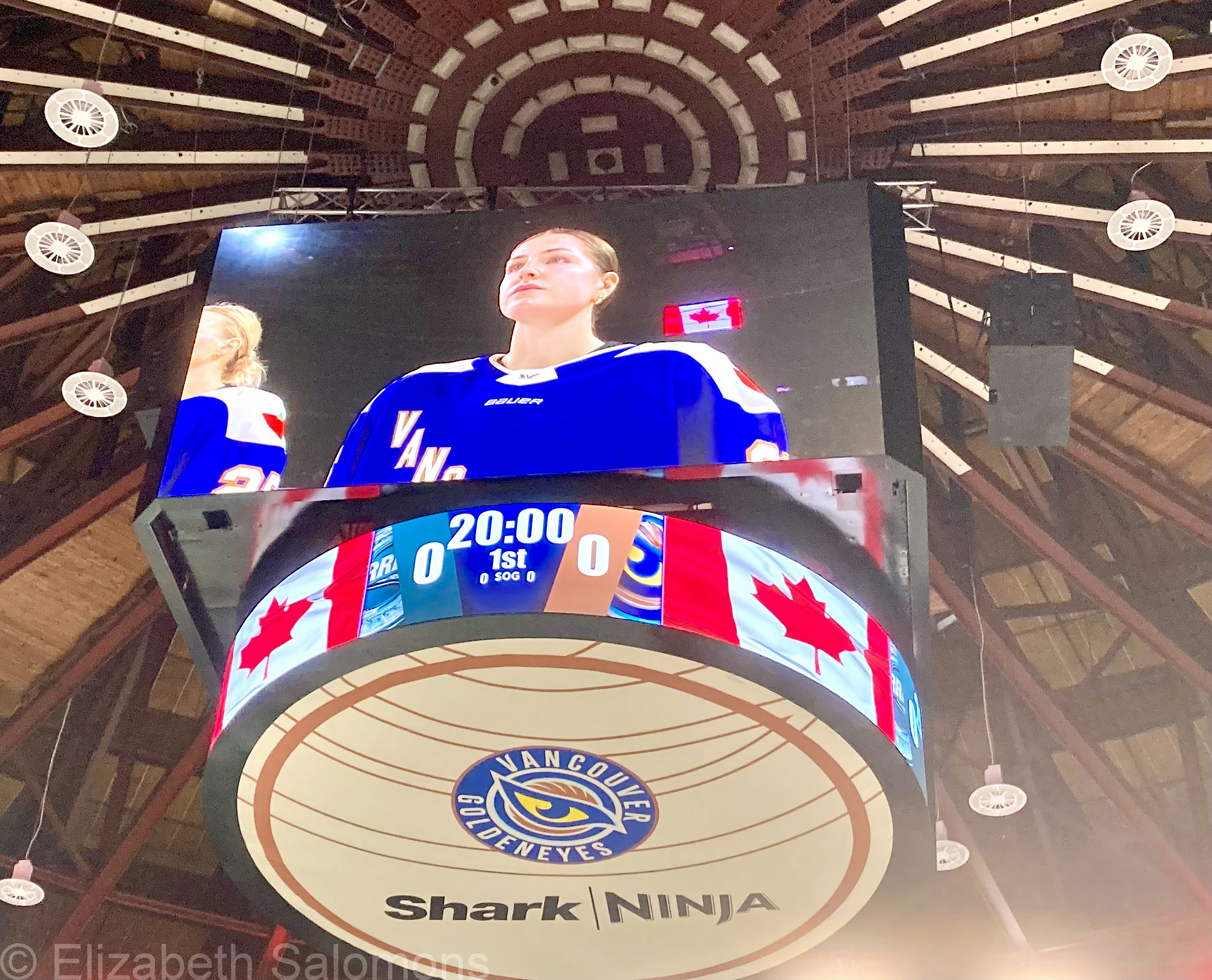

Vancouver Goldeneyes Home Opener

Vancouver gets behind its professional sports teams in a pretty big way. And now there’s a new team in town to cheer on. That would be the PWHL’s Vancouver Goldeneyes.

I was one of 14,958 lucky fans sitting in the Pacific Coliseum last night who got to watch the season home opener and the first game in franchise history. The atmosphere was electric.

The Goldeneyes are the first Professional Women’s Hockey League (PWHL) team to be an anchor tenant in their arena. Which means they are the only PWHL team that gets to play on ice branded with their team logo. It may seem like a small thing, but if you listen to the media interviews the players gave after the game, you realize, for them, it is huge.

These photos aren’t the greatest as I was shooting with a four-year old iPhone that’s pretty bad with distances. Even so, it was fun documenting a series of franchise “firsts” and I’m so glad I was there.

First sell-out game

First warm-up

First ceremonial puck drop

First national anthem

First game puck drop

First penalty

First win

Through My Lens: Alberta Highway 540

A couple of times a year, I make the trek from Vancouver to Calgary (by plane) then on to Lethbridge (by car) to visit family — as I did last weekend. But instead of taking Highway 2 all the way back to Calgary as I usually do, I decided to make a left turn somewhere north of Nanton and south of High River onto Highway 540. And I’m so glad I did.

I mean, c’mon. Just look.

World Series 2025

What a game. What a series.

Both of these things can be true: I haven’t watched a Blue Jays’ game since I moved from Toronto to Vancouver in 1998.

Also true: I remember exactly where I was when Joe Carter hit that home run (at a party hosted by my history professor where a bunch of us — including my prof — had decamped to the TV room to watch the game).

This week brought back so many great memories of how much fun it was living in Toronto in the early ’90s. It didn’t go our way last night, but there’s always next year.

Happy Birthday, Amsterdam!

As far as European cities go, 750 years is rather young, but that’s how old Amsterdam is. And today marks the final day of a year-long celebration of the city’s milestone birthday.

The reason Amsterdam was settled later than other parts of the country and the continent is because it simply was not possible to build on the land until its water issues were resolved. After the Amstel River was dammed (hence the name: Amstel + dam), a fishing village was established. The first documents to register Amsterdam’s existence date back to 1275. By the seventeenth century, it was an economic powerhouse and centre of trade and finance — what’s known as the Dutch Golden Age.

I really came to know and appreciate the city during my summer in Amsterdam. Here’s hoping I get to repeat the experience again someday.

Through My Lens: September Flowers

It’s raining today. And I can’t believe I’m saying this, but after a long, hot summer, it’s a relief to have some cooler temperatures again.

The flowers planted along English Bay are looking rather autumnal as well.

Through My Lens: Ruckle Park Sunrise

I was hoping for a weekend of sunrises like this one at Ruckle Park on Salt Spring Island. Alas, our planned weekend of camping by the sea had to be cancelled when one of our party came down with Covid. Five years on, it’s still safety first.

And I, for one, am OK with that.

Through My Lens: Ships and Foliage at Sunset

I’ve been a bit neglectful about posting lately. Because summer. (Who wants to be sitting at their computer when you can be outdoors?)

This is a favourite photo of mine; I took it as I walked along the seawall one warm August evening some years ago.