Through My Lens: Doors of Dublin

Not the best of photos, but it will do for Bloomsday, I should think.

This year is also the 100th anniversary of the publication of James Joyce’s Dubliners — a collection of short stories I’ve not looked at since my university days, but thoroughly enjoyed then.

Methinks it’s time I recommend to my Book Club that we read some Joyce.

Happy Birthday, William Shakespeare!

It’s his 450th birthday today ― the Bard’s, that is. I’ve been rummaging through my photos to see if I had any that link to William Shakespeare and I found this one. It’s of the Tower of London.

Richard III, considered by some to be one of Shakespeare’s greatest plays, was almost entirely set in London and several of its scenes take place in the Tower. You know the play. It’s the one that starts out with Richard talking about the end of his winter:

Now is the winter of our discontent

Made glorious summer by this sun of York

Richard doesn’t come off so well in the play. Shakespeare probably did more to malign his reputation than any historian. But never mind. It’s an entertaining play. And its setting gives me an excuse to post a photo.

Note the ravens in the photo. Six of them are kept at the Tower because legend has it that the Crown (Britain, too) would fall if the ravens were to ever leave the Tower.

A Book Smuggler, er, Travel Blogger Goes Through US Customs

You know how sometimes you have really odd conversations with customs officers? Like, right-out-of-the-twilight-zone odd?

The one I had with the American customs officer at Pacific Central Station (aka the Vancouver train station) last week, while I was en route to Seattle, was one of the oddest I’ve ever had. It went like this:

Customs Officer: And what do you do for a living?

Me: I’m a book editor.

Customs Officer: Oh! That must be an interesting job.

Me [pause]: It can be.

Customs Officer: Are you bringing any books to Seattle with you?

Me: Yes.

[confused look on customs officer’s face as he turns back to my declaration form to see what goods I’m declaring (none), at which point I realize he means am I bringing books to … sell? to … distribute? to … oh, I have no idea for what purpose he might think I want to bring books into his country, so I decide I better clarify the situation for him]

Me: I have books with me to read. I’ll be bringing those same books with me back to Canada.

Customs Officer [frowning]: We ask these questions for a reason, you know.

Me: You asked me if I had any books. And I do.

[customs officer doesn’t say another word, gives me back my passport, and waves me on through]

Since I was at a writing conference, I bought one or two (erm, six) books, as one would expect. And, since I don’t want to be arrested for book smuggling, I declared them to the Canadian customs officer upon my return to Canada after the weekend was over. As one would expect.

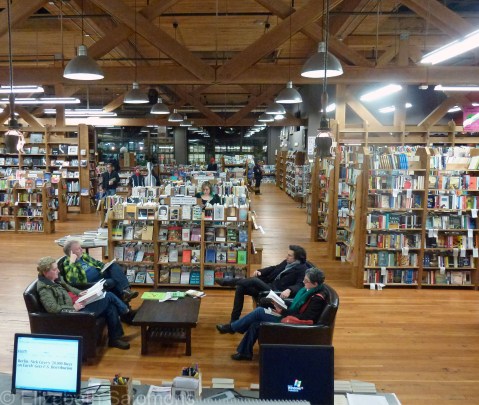

The Elliott Bay Book Company, Seattle

Through My Lens: Seattle Central Library

Here’s a photo of the funky escalators at the Seattle Central Library. I’ve been wanting to post more photos of this library ever since I photographed it when I was last in Seattle. I have three good reasons for posting one today.

- This week is Freedom to Read Week in Canada.

- I’m in Seattle.

- I’ve spent the past two days at the AWP Conference, the largest literary conference in North America. Which means I’ve spent the past two days listening to dozens of panelists talk about writing, reading, editing, and publishing. (Which, you might have guessed, is my kind of heaven.) Which also means I’ve got a whole list of authors to check out as soon as I can get myself back to my own library.

And so, a photo of a library is entirely appropriate for today. Enjoy.

Hemingway Home and Museum

‘Listen,’ I told him. ‘Don’t be so tough so early in the morning. I’m sure you’ve cut plenty of people’s throats. I haven’t even had my coffee yet.’ ― Ernest Hemingway, To Have and Have Not

Once upon a time, a Canadian twentysomething was registering for her senior year at a small liberal arts college somewhere in the American Midwest. Her timetable was jam-packed as she tried to squeeze in all the required courses she needed in order to graduate. When her advisor told her she had to fit in at least one American literature course (“you are not going to graduate with an English major from an American college without studying American literature!”), she was annoyed. Reluctantly, she registered for the course.

When she showed up to class, she discovered that the prof was a bore, the reading list a snore, and, to add insult to injury, every Friday afternoon she and her classmates were subjected to a reading quiz. A reading quiz?? What was this? High school?? In protest, the college student didn’t read any of the assigned novels. She managed to pass the course, albeit with the lowest grade of her academic career.

The summer following her college graduation, this college student (now college grad) picked up the unread American novels she had lugged back home to Canada. Since she was intentionally unemployed (as she called it), she had lots of time to read. So she read them all.

And that is how one Canadian college grad discovered Ernest Hemingway. Hemingway!! Who knew? For many years afterwards, she fervently declared to anyone who asked that For Whom the Bell Tolls was one of the best novels she had ever read. She was chuffed when a writing teacher once praised her work as being “just like Hemingway’s!” (She didn’t believe him, but she was chuffed.) And when the college grad (now editor and writer) found herself many years later on holiday in Key West, she made a beeline for the Hemingway Home and Museum.

Ernest Hemingway lived on and off in Key West from 1928 until 1940 with wife # 2 (Pauline Pfeiffer). They bought the 3000-square-foot house in 1931; it was, and is, the largest residential property in Key West. In 1937, after Hemingway took off for Spain to report on the Spanish Civil War with the woman who would become wife # 3 (Martha Gellhorn), Pauline built a swimming pool over his beloved boxing ring. After the divorce, Pauline continued to live in the Key West house with their two sons until her death in 1951.

The Hemingway Home and Museum opened in 1964. For the past 50 years, knowledgeable and affable guides have taken tourists and book-lovers alike through the home and garden, which is still furnished much as it was when the Hemingways lived there. Of particular note are the cats that live on the property; there are over 50 of them, all well fed and well looked after. Descended from a six-toed cat given to Hemingway by a sea captain, about half of them have six toes on their front paws.

Hemingway’s Key West period was his most prolific. In spite of the amount of time he spent fishing and drinking, he was able to write two novels, To Have and Have Not and For Whom the Bell Tolls, and many short stories including “The Snows of Kilimanjaro.”

Hemingway had a writing studio on the second floor of a carriage house behind the main house.

The studio overlooked the pool.

Kids, this is a typewriter. It’s what people used to type with before there were computers.

Although the gate is left wide open, none of the cats on the Hemingway property ever wander off.

In fact, the museum staff has to be vigilant to keep the neighbourhood cats from moving in.

Armchair Traveller: On Rue Tatin

How many shopping days until Christmas? I think I have time to squeeze in another book recommendation.

How many shopping days until Christmas? I think I have time to squeeze in another book recommendation.

This one is by another American cookbook author who transplants herself to France, but she doesn’t write about cooking in the World’s Most Glorious ― and Perplexing ― City. Instead, she and her family live (and cook and eat) in a small village in Normandy.

On Rue Tatin by Susan Herrmann Loomis is part travel memoir, part cookbook. There is one long tedious chapter to get through that describes her history with France and how she and her husband came to live in Normandy, but after that the book picks up its pace. Many pages are devoted to their struggles (and expenses) of renovating the house they bought beside the Romanesque/Gothic village church into a family home. The building was a convent for three hundred years, then an antique shop; I dread to think of what it looked like when she first set foot inside. It is in this convent-turned-home that she also teaches week-long classes at her cooking school, also named On Rue Tatin.

Although the first chapter of On Rue Tatin almost made me put the book down (what was her editor thinking?), Normandy is an underrated region of France and for that reason alone I recommend giving the book a read. I also have to ’fess up that Loomis’s assessment of the amount of rain Normandy is known for made me laugh: as a former Seattleite, she assured her readers it was nothing. That was enough to convince me that I would feel right at home in Normandy. And her recipes are enticing enough that I have already decided my next cooking class will be on Norman cuisine (here in Vancouver, alas, not in Normandy). But I can already smell the tarte tatin I will be baking.

Armchair Traveller: The Sweet Life in Paris

Are you still searching for the perfect Christmas gift for the armchair traveller in your life? Perhaps you could use a suggestion for your own holiday reading. Either way, here’s a book recommendation for you: The Sweet Life in Paris by David Lebovitz.

Are you still searching for the perfect Christmas gift for the armchair traveller in your life? Perhaps you could use a suggestion for your own holiday reading. Either way, here’s a book recommendation for you: The Sweet Life in Paris by David Lebovitz.

I discovered David Lebovitz’s writing through his blog called, appropriately enough, Living the Sweet Life in Paris. But even if I had never heard of the guy (or his blog), I would have grabbed the book off the store shelf on the merit of its subtitle alone: Delicious Adventures in the World’s Most Glorious ― and Perplexing ― City.

David Lebovitz is a San-Francisco-pastry-chef-turned-cookbook-writer who starts life over in Paris following the unexpected death of his long-time partner ― a move he describes as “an opportunity to flip over the Etch A Sketch” of his life. Once in Paris, his writing shifts and his books expand from simply recipes to an examination ― centred around food, of course ― of all the ups and downs of living in Paris.

The Sweet Life in Paris is the result. It’s a book of short essays about daily life in Paris, followed by an appropriate recipe. Some of the links are tenuous, like when Lebovitz follows a description of French plumbing woes with a recipe for a meringue dessert called Floating Island. (The connection between the two? He recommends not flushing the meringue down the toilet if it doesn’t turn out.) Others are bang on, like his recipes for Chocolate Mousse that accompany the story of how he discovered the secret to dealing with French bureaucrats is to bribe them with free copies of his cookbooks.

Lebovitz’s credibility shot up when I read his recommendation that, if you don’t like anchovies, be sure to try them fresh in Collioure on the Mediterranean coast. I’ve eaten fresh anchovies in Collioure ― they would convert any non-believer.

But while Lebovitz’s descriptions of food in The Sweet Life in Paris are mouth-watering, as are his recipes, what I appreciate most about this book is his ability to see the funny in the incredibly frustrating idiosyncrasies of Parisian life. I’m with him 100% as he puzzles over why European washing machines take two hours to wash a load of laundry that would take North American machines a mere 40 minutes. Most of all, I wish I’d known his system for navigating the aisles of a Parisian supermarket before I spent a winter in Paris:

I hold [my basket] in front of me as I walk, like the prow of a battleship, to clear the way. That doesn’t always work, as Parisians don’t like to move or back up for anyone, no matter what. So sometimes I hide my basket behind me, then heave it forward at the last moment; the element of surprise gives them no time to plan a counteroffensive, and when the coast is suddenly clear, I made a break for it.

I lost count of how many times I had to sidestep, trip over, or squeeze past Parisians who refused to budge an inch in the narrow aisles of Monoprix or Carrefour. Now I can’t wait to go back and try out Lebovitz’s technique.

Even if you’ve never been to Paris and don’t know the difference between a pastry brush and a pastry blender, pick up a copy of The Sweet Life in Paris. It’s good for the laughs.

Armchair Traveller: Hallowed Ground

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate — we can not consecrate — we can not hallow — this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our power to add or detract. — President Abraham Lincoln

Last post I wrote that you couldn’t tour the Gettysburg battlefields on foot ― not in an afternoon, that is. But should you be motivated to attempt it, I highly recommend taking along James M. McPherson’s book, Hallowed Ground: A Walk at Gettysburg.

Last post I wrote that you couldn’t tour the Gettysburg battlefields on foot ― not in an afternoon, that is. But should you be motivated to attempt it, I highly recommend taking along James M. McPherson’s book, Hallowed Ground: A Walk at Gettysburg.

Professor emeritus of Princeton University and author of the Pulitzer Prize–winning book Battle Cry of Freedom, McPherson is considered the finest Civil War historian in the world (according to his book’s flap copy). Hallowed Ground takes its title from the words Abraham Lincoln spoke in his Gettysburg Address (quoted at the top of this blog post).

As a guidebook on its own, Hallowed Ground lacks maps and precise details about how to navigate the park. But as a means of providing context, I found Hallowed Ground invaluable reading prior to my tour of Gettysburg. McPherson explains in simple lay language how the battle changed the course of the Civil War, and its significance in American history. The book includes anecdotes of the author’s walks around key positions of the battle, such as Seminary Ridge, the Peach Orchard, and Little Round Top, as well as stories about the various monuments and statues.

McPherson has led countless tours for students and others at Gettysburg; with a little imagination, reading his book is like being on one of his tours.

George Peabody Library

This week is Freedom to Read Week in Canada, so I thought it was high time I wrote another post about a book. Or, perhaps, many thousands of books. Like the ones in this library.

There are libraries. And then … well … and then there’s the George Peabody Library.

The George Peabody Library is one of the libraries of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. It’s housed in a stunning building designed by architect Edmund Lind and has been open to the public since 1873. The library is named after George Peabody, the American–British financier and philanthropist who provided the funds for the library’s founding in 1857.

The collection consists of over 300,000 books, mostly from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and specializes in all the good stuff: archaeology, British art and architecture, British and American history, English and American literature, Romance languages and literature, Greek and Latin classics, history of science, geography, and ― wait for it ― exploration and travel.

There are a lot of cool-looking libraries on this planet. As if I need another reason to travel, I plan to photograph as many of them as I can.

Armchair Traveller: Under the Tuscan Sun

Some twenty years ago, Frances Mayes bought an abandoned villa near Cortona, Italy. She and her husband spent three summers renovating it, and then she wrote a book. The travel memoir genre has never been the same since.

Some twenty years ago, Frances Mayes bought an abandoned villa near Cortona, Italy. She and her husband spent three summers renovating it, and then she wrote a book. The travel memoir genre has never been the same since.

Published in 1996, Under the Tuscan Sun was on the New York Times Best Sellers List for over two and a half years. In 1998, I spent a week with a friend who was studying art in Siena for the summer. She was reading the book. All of her classmates were reading the book. Every bookstore I walked by that week had Under the Tuscan Sun on display in its window. In the aftermath of the book’s success (as well as that of Peter Mayle’s A Year in Provence a few years earlier), there’s been a rush to publish hundreds, if not thousands, of memoirs about ex-pats buying and restoring houses all along the Mediterranean. The saturation of the genre may be the reason for some of the criticism levied today against authors like Mayes and Mayle. The truth is: ex-pats were buying up property in southern Europe long before these two authors. They simply came up with the idea of writing about it ― and they did it brilliantly.

Mayes starts her book off as a love poem to Tuscany, and to the home described as “a house and the land it takes two oxen two days to plow” in the legal documents she and her husband signed upon purchase. She describes evenings “when the light turns that luminous gold I wish I could bottle and keep.” She includes recipes, and to show her growing interest in the cuisine of the region, she writes paragraphs such as these:

… cooking seems to take less time because the quality of the food is so fine that only the simplest preparations are called for. Zucchini has a real taste. Chard, sautéed with a little garlic, is amazing. Fruit does not come with stickers; vegetables are not waxed or irradiated, and the taste is truly different.

Under the Tuscan Sun has a little bit of everything: interior design, recipes, gardening, history, travelogue. If you’re looking for lots of detail on any one of those subjects, this is not the book for you. But if you think you might enjoy reading how an American poet and creative writing teacher fell in love with a crumbling villa in the middle of Tuscany, then this book is worth a read.