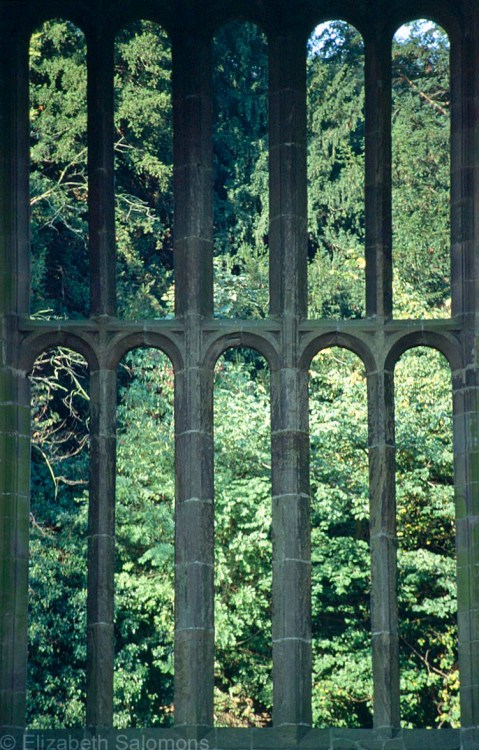

Through My Lens: Fountains Abbey Windows

For Palm Sunday, I’m posting a photo of a wall of windows from Fountains Abbey. These windows are located on the bottom level of the abbey’s tower, which was built not long before the abbey was surrendered to the Crown. As I explained last Sunday, after the surrender, the lead and glass were removed from all of the abbey’s windows, allowing in the elements and causing the abbey to quickly fall into ruin.

The Crown sold Fountains Abbey to a merchant from London. Eventually, it was purchased by Sir Stephen Proctor, who used stone from the abbey to build a home for his family. It took from 1598 until 1611 to build that house, which he named Fountains Hall.

What was left of the abbey became the estate’s “folly” — essentially a giant lawn ornament. Such features were common in formal English gardens.

Since 1983, Fountains Abbey has been owned by the National Trust. It was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1986.

Through My Lens: Fountains Abbey Narthex

Here is a photo of the narthex of Fountains Abbey, which I am posting for the Fifth Sunday of Lent. A narthex is the entrance to a church. Nowadays, we usually call it a foyer.

You get an idea of the size of the church at Fountains Abbey from this photo. It wasn’t until I visited this abbey that I began to understand why so many of England’s abbeys lie in ruins. Which is ironic, considering that Fountains Abbey is one of the best-preserved abbeys in all of England.

It’s because once you take away the roof, the building doesn’t stand a chance against the unpredictable English weather.

Why is there no roof? That’s easy. When the deed of surrender was signed at Fountains Abbey in 1539, the abbey had to be made unfit for worship. The roof was torn off, and the windows were stripped of their lead and glass. Some of the stone was carted off to be used for building projects elsewhere; the rest was worn down by the elements. During the Dissolution, many of the abbeys were also burned to ensure that the monks would leave.

The Dissolution came about because of Henry VIII’s break with the Catholic Church. More than 900 religious houses — home to some 12,000 people — were destroyed between 1536 and 1541. Initially, the proceeds from the monasteries was intended to provide an income for the Crown, but eventually many of them were sold off to fund Henry’s wars.

Canada 150: Tr’ochëk

Here is one last photo from North of 60. This is fireweed, the official flower of Yukon. It takes its name from the fact that it is one of the first plants to grow after a forest fire.

I took this photo at Tr’ochëk, a former settlement of the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation. It’s also known as Moosehide. Located about 5 km down the Yukon River from Dawson City, the settlement was abandoned in the 1960s after its only school was closed. Today, it is an important gathering place and a seasonal fishing camp for the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation.

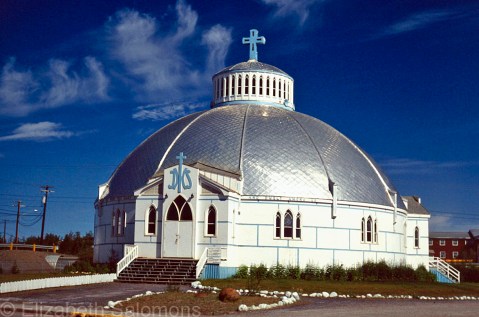

Canada 150: Inuvik

Our road trip up the Dempster led us, eventually, to Inuvik. Located 200 km north of the Arctic Circle, Inuvik was built in the 1950s in its present location in the Mackenzie River delta to function as the region’s administrative centre.

Inuvik is the northernmost point of Canada that I’ve ever been to. Until this year, it was also the northernmost point in Canada that you could drive to in the summer. In the winter, the Dempster Highway continues north to Tuktoyaktuk for another 194 km along an ice road formed on the channels of the Mackenzie River delta and the Arctic Ocean. This ice road was only open during the winters, but is being replaced by a new all-season road scheduled to be finished by the end of next summer.

Our Lady of Victory Parish, or the Igloo Church as it is often called, is the community’s Catholic church. It was designed by Brother Maurice Larocque, a missionary from Quebec who spent his entire ministry working in the North. Before he became a priest, he was a carpenter, and he used his skills to design a church that reflected the people who would worship in it. The church was built in the shape of an igloo to be able to deal with the shifting permafrost it stands on.

The Igloo Church is the most photographed building in Inuvik. Naturally, I had to take a photo, too.

Through My Lens: Fountains Abbey Nave

Without the lay brothers who built the abbey and did all the daily chores necessary to keep body and soul together, Fountains Abbey would never have become as wealthy as it did. At the time of Dissolution, the abbey’s land holdings had increased to 500 acres, making it one of the richest religious houses in England.

Which also made Fountains Abbey awfully attractive to Henry VIII, who used the proceeds from dismantling England’s abbeys to fund his military campaigns. (More on that next week.)

For today, the Fourth Sunday of Lent, I’m posting a photo of the nave of Fountains Abbey. Imagine, if you will, that the roof is still in place and the monks are singing and chanting as they process down this nave towards the Great East Window.

Canada 150: Tsiigehtchic

This photo is of Tsiigehtchic, which is where the Mackenzie River meets the Arctic Red River, and where the Dempster Highway crosses the Mackenzie River. Vehicles cross by ferry in the summer. In the winter, there is an ice crossing.

Tsiigehtchic is the Gwich’in word for “mouth of the iron river.” Iron river (Tsiigehnjik) is their name for the Arctic Red River.

Nagwichoonjik, or “river flowing through a big country,” is what the Gwich’in call the Mackenzie River. The Dene call it Deh Cho, which means “big river.” And its Inuvialuktun name is Kuukpak, which means “great river.”

In case there is any doubt, the Mackenzie is a big river. At 4241 km long, it’s the largest and longest river in Canada, and the second largest and longest in North America. (Only the Mississippi is longer.) The Mackenzie River’s watershed covers one-fifth of Canada’s land mass.

The river got its English name from Alexander Mackenzie, who followed its length to the Arctic Ocean in 1789. He hoped the river would empty into the Pacific Ocean. When he realized it did not, he is said to have named it Disappointment River.

That’s an awful lot of names for one river. Whatever you call it, it’s worth crossing.

Through My Lens: Fountains Abbey Cellarium

For the Third Sunday of Lent, I’m posting a photo of the cellarium at Fountains Abbey. Cellarium is a fancy monasterial word for “storeroom,” and this one was located beneath the dormitory where the lay brothers slept. It was used mainly to store food.

Fountains Abbey had two orders of monks: choir brothers and lay brothers. The choir brothers did all the praying and singing, while the lay brothers did all the manual labour required to run the abbey, including stonework and metalwork, tanning hides and making shoes, brewing and baking, and herding sheep.

Through My Lens: Fountains Abbey Great East Window

Fountains Abbey was founded by 13 rebel Benedictine monks from St. Mary’s Abbey in York. They were sent packing because they wanted to live by a stricter rule than the Rule of St. Benedict that the monks in York followed.

The rebel monks were given 70 acres of land in a valley near Ripon in North Yorkshire. They decided to establish a Cistercian order, which is a French monastic order. Cistercian monks supported themselves by farming. The land near Ripon had everything the rebel monks needed: a valley setting to shelter them from the North Yorkshire weather, stone and timber for building, and plenty of water. The name of the abbey, St. Mary of Fountains, is thought to have originated from some nearby springs.

Not long after founding their abbey, the monks built a church out of stone. The Great East Window above the Chapel of Nine Altars behind the High Altar is featured in this photo, which I am posting for the Second Sunday of Lent.

Through My Lens: Fountains Abbey and the River Skell

For this year’s Lenten series, I’m going to follow up on last year’s series of photos of Mission Abbey with photos of another abbey. This time, though, we are once again back on the other side of the pond.

This year’s abbey is Fountains Abbey in North Yorkshire, England. It was founded in 1132 and operated as a religious house until 1539 when it was surrendered to the Crown during the Dissolution of the Monasteries under Henry VIII.

For the First Sunday of Lent, here is the view of Fountains Abbey when walking towards it from the west. All that is visible of the abbey is the church tower, which is reflected in the River Skell.

Anna’s Hummingbird

I took this photo of an Anna’s Hummingbird a few weeks ago during our last snowstorm. I was housebound during that storm because I was hanging out in Solo. If you look closely, you can see that the water in the feeder is almost frozen solid. I’m sure that hummingbird was as confused as I was by the cold weather.

Why am I posting this photo today? Because this morning I spent nearly an hour watching big fat snowflakes fall from the sky.

C’mon. It’s almost March. More snow??

Vancouver has had twice as much snow this winter as Edmonton where it’s winter seven months of the year. (I can say that because I grew up in Edmonton. I know winter. Er … I used to know winter.)

Anna’s Hummingbirds do not migrate south from Vancouver for the winter, thanks to the proliferation of backyard feeders like this one. I still can’t get my head around the fact that hummingbirds are here year-round.

I just hope all that hovering they do kept those tiny birds warm this winter.