Wood Duck

A couple of years ago when I wasn’t working much and had time to spare, I helped my brother out by taking his one-year-old daughter for the day every couple of weeks or so. My home isn’t set up for napping toddlers and so, after lunch, we’d go for a long walk in her stroller. We both got some fresh air, and she got a decent nap.

Invariably on those afternoons, I took my niece to Lost Lagoon to see the ducks. That’s when I first noticed the incredible variety of duck species in Stanley Park ― something I had never paid attention to before. At the time, I thought it was due to the spring migration.

Fast forward a couple of years to my Florida holiday, which is when I first began to think there might be something to this birding business. I mean, hey, birding involves three things I absolutely adore: the outdoors, photography, and (oh yeah, baby) lists.

After that Florida trip, I began to pay more attention to the birds in Stanley Park. I discovered that English Bay and Burrard Inlet (aka my backyard) is an IBA (Important Bird Area). I also discovered that the ducks I noticed during the long walks with my niece weren’t in the midst of their spring migration, but actually spend the entire winter in Stanley Park.

In short: the best time to go birding in Vancouver is during the winter months.

And so, another sign that fall is well and truly here is the return of our wintering water fowl to Stanley Park. I saw my first Wood Duck of the season last week when I was ambling around Beaver Lake.

Of all the ducks that spend their winters in Stanley Park, the Wood Duck is the prettiest of them all, thanks to its vibrant colours and markings. Unlike most ducks, Wood Ducks like to hang out near wooded areas, which is why the best place to spot them in the park is along the brushy perimeters of Beaver Lake and Lost Lagoon.

I don’t take my niece to see the ducks at Lost Lagoon anymore; she outgrew her stroller, no longer needs a nap, and now lives in another province. But here’s a pro-tip from a novice birder: if you have the chance to explore Lost Lagoon during the winter, grab it. You’ll have it all to yourself, except for, you know, the other birders.

Through My Lens: Stanley Park in Fall

It’s well and truly fall again. Here is a photo I took this past week while walking through Stanley Park. The path is called Ravine Trail, and it gets you from the seawall by Burrard Inlet to Beaver Lake. I think it’s one of the prettiest walks in the park.

Road Trip: Crowsnest Highway

I’ve written before how my road trips are few and far between, but that every once in a while I do switch it up and get behind the wheel of a rental car to admire the scenery through a windshield. Such was the case last summer when I chose to drive from Vancouver to Alberta and back. There were a number of reasons why I decided to drive, but not the least of which was that I’ve never driven the Crowsnest Highway. I was eager to explore a new corner of my home province.

And you know what? The Crowsnest Highway is unbelievably beautiful. Totally. Blew. My. Mind.

When I have an experience like that in my own backyard, I always have to ask myself: why ever do I travel outside of Canada when there is so much beauty right here?

Rhetorical question, people. Moving right along …

The Crowsnest Highway takes its name from the Crowsnest Pass, which is a valley that crosses the Rockies just north of the US–Canada border. The pass got its name from Crowsnest Mountain, which the Plains Cree named after the many large black birds nesting in the area. They were likely ravens, though, not crows.

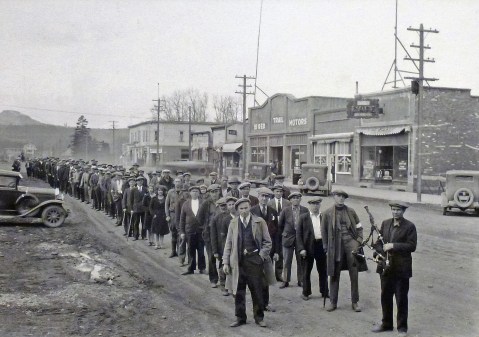

The Crowsnest Highway is also known as Highway 3. Back in the nineteenth century, there was a gold rush trail through the Kootenay Mountains and a highway ― the Crowsnest ― was built along the remnants of that trail in 1932.

I got on the Crowsnest Highway near Pincher Creek, Alberta, after my visit to Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump, and I followed it, mouth agape in a state of constant awe, all the way west to Osoyoos, British Columbia. Here is a quick photo tour. (Click on the first photo at top left to open the slide show.)

Most folks, including myself, usually take the Trans-Canada Highway from Calgary to Vancouver. It, too, is a scenic drive ― one of the best on the planet, in my humble opinion. But if you have the time and the inclination to go slow,* check out the Crowsnest Highway. It’s well worth a look.

*The Crowsnest is about 250 km longer than the Trans-Canada, and, unlike the Trans-Canada, is not twinned, so it is a longer and slower route.

Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump

After Calgary, I had one last stop to make before I turned my rental car west towards home.

Located west of Fort MacLeod (which is south of Calgary), Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump is one of the world’s largest and best preserved buffalo jumps. It was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1981. That’s kind of a big deal ― being on the list puts Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump on par with the Egyptian pyramids and the Galapagos Islands. There are only 17 World Heritage Sites in all of Canada.

Essentially, Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump is a vast archeological site. The research that has been done on the site gives us modern-day folks evidence of how the Plains People hunted the buffalo in centuries past. We now know that Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump was in use for about 6000 years up until the mid-1800s.

What’s a buffalo jump, you ask? It’s a cliff over which the buffalo were, well, let’s say, encouraged to jump off. The hunters would disguise themselves with wolf skins and start a stampede of the buffalo herd, driving them towards the cliff.

After the buffalo ran over the cliff, the hunters were then able to go below and butcher the dead buffalo.

Archaeologists think that at least ten metres of buffalo bones still lie buried below the surface of the prairie at Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump.

There is an impressive five-level interpretive centre built into the side of the cliff at Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump. The exhibits will answer your every question about buffalo jumps.

In addition to the interpretive centre and the well-fenced view point above the buffalo jump, there is a short trail below the jump that provides you with some magnificent views over the prairie.

The wind is keen ― I was impressed by its power and by how much noise it makes. If you look carefully at this next photo, you can see a row of wind turbines in the upper left corner ― these are ubiquitous in this part of the province.

I’m so in love with this flat horizon.

Oh ― and the name? It’s not about smashed buffalo heads. It was the name given to a small boy who wanted to see the buffalo jump over the cliff, but who got way too close. He was crushed by the falling animals.

Black-billed Magpie

I’ve been trying to photograph this bird for a while, but hadn’t any luck until my most recent visit to Alberta. This is a Black-billed Magpie ― almost never seen in Vancouver, but common to Alberta.

I’m in a definite minority in thinking that magpies are beautiful because any Albertan will pull up their nose and say (as some have done to me), “Why are you taking a picture of a magpie? Don’t you know they’re scavengers?”

Apparently magpies are from the same family as crows. I have strong feelings about crows because they typically like to dive-bomb me as I walk through my neighbourhood. So maybe I should have more empathy for my Alberta relatives and their strong feelings about magpies ― apparently magpies are also known to be dive-bombers.

The Glenbow

Calgary’s got yet another thing going for it, and that’s the Glenbow. The Glenbow is an art and history museum I’ve long heard about because it’s not just a museum, it’s also a library and archive. Archives are like crack for historians, and the Glenbow is Canada’s largest non-governmental archive.

Those archives contain unpublished diaries, letters, and minute books of thousands of Alberta families, organizations, and businesses. Its library has more than 100,000 books, pamphlets, journals, newspapers, and government documents related to the history of Western Canada. And its image collection includes photographs, posters, and cartoons that tell the story of the Canadian West from the 1870s to the 1990s.

Whew! Makes me want to go research a book!

What the Glenbow Museum does particularly well is tell the story of southern Alberta, including its first peoples.

It also has a permanent exhibit with the unlikely title of Mavericks: An Incorrigible History of Alberta. It’s about some of the famous (and infamous) Albertans who shaped the province’s history over the past 150 years. Did you know the fellow who discovered oil in Leduc in 1947 ― that would be Ted Link who worked for Imperial Oil ― was told by his head office in Toronto to stop drilling? Head office had given up on the search for oil. Mr. Link, convinced that the entire province was lying on a bed of sedimentary rock (a possible source of hydrocarbons), pretended he hadn’t received the order. Two days later, Leduc No. 2 blew in and changed the course of the province’s history.

Want to learn about more stories like this? Be sure to stop in at the Glenbow the next time you’re in Calgary.

The Famous Five

Calgary has one more impressive feature that I want to post about, and that is its monument to the Famous Five.

No, I’m not talking about the child sleuths made famous by English children’s author, Enid Blyton. I’m talking about the five Alberta women who took the Canadian government to court when they were told their gender made them ineligible to sit as senators.

It all started when Emily Murphy, the first female magistrate in the British Empire, was recommended for a Senate seat in 1917. Prime Minister Robert Borden refused to appoint her, saying that he was prevented from doing so by the constitution. He was referring to Section 24 of the British North American Act, 1867, which states the following:

The Governor General shall … summon qualified Persons to the Senate; and, subject to the Provisions of this Act, every Person so summoned shall become and be a Member of the Senate and a Senator.”

“Qualified persons,” said the prime minster, referred only to men. He had a problem, though. Emily Murphy had popular support ― a lot of support. Half a million Canadians signed petitions and wrote letters. And Prime Minister Borden needed the vote of Canadian women to stay in office. So, over the next decade, four consecutive federal governments declared their support for Emily Murphy, but each insisted it was prevented from appointing her to the Senate because of the constitution.

After ten years of no progress, Murphy tried another tactic. The Supreme Court allowed any five citizens acting together to appeal for clarification on any point of the constitution. And so, in 1927, the following question was put to the Supreme Court of Canada:

Does the word ‘Persons’ in Section 24 of the British North American Act, 1867, include female persons?”

The court ruled no, after which the case became known as the Persons Case. The Famous Five then appealed to the British Privy Council (at that time the court of final appeal for Canadians) and the ruling was overturned on October 18, 1929. Canadian women were declared persons and declared eligible to sit as members of the Senate of Canada.

History geek that I am, I was so pleased to come across the monument to the Famous Five in Calgary’s Olympic Park. The statues were dedicated on October 18, 1999 ― seventy years after the Famous Five won their case ― and a duplicate of the monument stands on Parliament Hill in Ottawa.

Why was it such a big deal that women be able to sit as senators, you ask (other than, you know, the obvious issue of equal rights)?

It’s because until 1968 there was no divorce law in either Quebec or Newfoundland. Residents of those two provinces had to request a private Act of Parliament to dissolve their marriages, a procedure that was usually handed off to the Senate. If the Senate was going to decide family law, women needed representation to ensure equal treatment with men.

Incidentally, I also learned through my research for this post that people were complaining already back in the 1920s about how useless the Senate was and arguing that its members should be elected, not appointed. And, yes, there were federal political parties calling for its abolition.

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose, n’est-ce pas?

Calgary

Confession time.

Calgary is uncharted territory for me. Although I grew up in Alberta, before last month, I think I had visited the province’s largest city once, maybe twice, not counting the times I’ve flown or driven through it.

Even last month’s visit was less than 48 hours long. So I make no claim to know the city, but I can say this: what little I’ve seen, I like.

Here’s what impressed me:

# 1: It has Chinooks. These warm winds that swoop down over the prairies from the Rockies can melt a winter’s worth of snow in a day. We had them occasionally in Edmonton, where I grew up, but they are much more frequent in southern Alberta. Chinooks are a welcome respite from the cold Arctic air that usually blankets the province during the seemingly never-ending winters. What I didn’t realize is they occur year round. My first morning in Calgary, I looked out the window, saw a menacing storm cloud, and wondered aloud if it was going to rain. My sister took one quick look, then enlightened me. “That’s a Chinook arch,” she said.

Cool.

# 2: It’s got not just one, but two rivers. And the one I got up close and personal with has lovely parks alongside it.

I say “up close and personal” because the Bow River is pretty much at street level, which seems strange to me. I’m used to the North Saskatchewan River’s deep valley that neatly bisects Edmonton into a north side and a south side. It’s so much easier to understand how devastating the 2013 floods were for Calgary when you see the geography of its rivers firsthand.

# 3: It’s got a CTrain. I love that it’s a street-level train, rather than a monstrous elevated Skytrain like in Vancouver.

# 4: It celebrates its frontier history in a big way. Not only does it host the “greatest outdoor show on Earth” (another confession: I’ve never been to the Calgary Stampede), but just look at the number of thoroughfares named “trail” ― a reminder of the city’s original wagon trails. Macleod Trail goes south towards Fort Macleod; Edmonton Trail goes north. And then there’s Crowchild Trail, Stoney Trail, and the big one: Deerfoot Trail (named after a fast-footed Niitsitapi man who was known for his speed and endurance back in the 1880s).

# 5: It’s got Stephen Avenue, a well-manicured pedestrian mall smack in the middle of its downtown core, which does a nice job of melding the old with the new.

# 6: It’s even got bike lanes!

# 7: And last, but not least, it treats its canine population with a goodly amount of respect.

So there you have it: my whistle-stop tour of Calgary. Hopefully it’s only the first of many.

Through My Lens: Boom Lake

Wait? How did that happen?

It’s closing in on the end of September and I am way behind on posting about last month’s road trip to Alberta and back. Waaaay behind.

It’s not like I don’t know what to write about. I may even have a photo or two to post as well.

Here’s one. This is Boom Lake in Banff National Park, which is accessible by an easy 5 km hike from Highway 93. That’s not fog ― it’s smoke from last month’s wildfires in Washington state.

Yoho National Park

Here’s the thing I discovered about Banff National Park during my visit last month.

It’s operating at capacity.

I don’t mean it’s super crowded and chock-full of tourists. I mean there is, quite simply, no more room. Every campsite is filled, every hotel room is booked, and the streets of Banff townsite are gridlock by noon, as are the access roads to Lake Louise and Moraine Lake.

So what solution to the madness does someone who has just driven from Vancouver to Banff suggest to her family?

That they head across the Alberta–BC border to Yoho National Park.

Yoho was created a national park in 1886, just a year after Banff. It’s slightly over 500 square miles, about a fifth of the size of Banff, but it packs just as much awe and wonder ― in fact, its name, Yoho, is a Cree expression of wonder.

Just like in Banff, there is a wide assortment of hiking to do in Yoho, both short day hikes and longer overnight hikes in the back country.

And, just like in Banff, there are photo ops. Gazillions of photo ops.

Here is one. This is Takakkaw Falls. Takakkaw is another Cree expression ― it means “it is magnificent.” (My brother and sisters and I had a lot of fun with the word “takakkaw” back in the last century when we were little kids.)

Here’s another. This is the Natural Bridge, which straddles the Kicking Horse River. I also remember coming here when I was little, and I remember how fascinated I was by the origin of the name “Kicking Horse River.” James Hector named it that after getting kicked by his pack horse. Hector was a member of the Palliser Expedition, a group of men surveying possible routes for the Canadian Pacific Railway. They reached the Kicking Horse River in 1858.

Here’s a look at the Natural Bridge from another angle.

And here’s a closer look at the mighty Kicking Horse River. That’s Mount Stephen behind.

Just down the road from the Natural Bridge is what’s known as the Meeting of the Waters. It’s the confluence of the Yoho River (at left, in the photo below) and the Kicking Horse River (dead ahead). You only need to stand here for a second or two to be overwhelmed by the power of these two rivers.

Turn to the right, and you have this view.

So, here’s my tip of the summer: the next time you can’t get close to Lake Louise, get back on the Trans-Canada Highway and drive another twenty minutes west to Yoho National Park. You won’t regret it.