Canada 150: Hopewell Rocks

I’m nearing the end of my Canada 150 series, but it’s only now that I’ve reached leg two of my cross-Canada road trip. (Remember, I’m the one who doesn’t think it’s cheating if you break a cross-Canada road trip down into manageable chunks. Leg one of my road trip was from Vancouver to Toronto; a few years later I did Toronto to Cape Breton (that would be leg two); and a year after that was leg three, when I drove from Edmonton to Inuvik.)

On the way from Toronto to Cape Breton, we stopped off at Hopewell Rocks. These sea stacks are on the New Brunswick side of the Bay of Fundy. The Bay of Fundy is known for its tidal ranges, which are the highest anywhere in the world — sometimes as much as 16 metres or the height of a four-storey building. Those powerful tides have eroded the soft sandstone along the shoreline of the bay and created these rock formations.

We didn’t stick around long enough to watch the tide to come in, but if we had, we would have seen how only the tops of these rocks are visible at high tide.

Canadian National Vimy Memorial

I’m going to start this post off with a bunch of numbers.

Here’s one: 11.

Every year, at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month, we remember.

Here’s another number: 3598.

That’s the number of Canadian soldiers who lost their lives at Vimy Ridge, a battle that was commemorated with 100th anniversary ceremonies last April. Another 7000 soldiers were wounded.

And here’s one more number: 1.

That’s the number of graves my nieces and I set out to look for last summer when we visited Canadian Cemetery No. 2 at the Canadian National Vimy Memorial. It’s a big cemetery, but we found the grave in minutes.

The grave we were looking for was this one.

This Cape Breton soldier was the great-grand-uncle of the wife of a friend of a friend of mine. How many degrees of separation between that soldier and me? I told my nieces it was five and they were all over the idea that they were the sixth degree. More numbers. Whatever the degree of separation, knowing that I knew someone who knew someone who was related to a Canadian soldier buried at Vimy Ridge gave all of us a personal connection to those horrific events of 100 years ago.

I have more numbers. The Vimy Monument stands at the highest point of Vimy Ridge — the piece of land that was fought over by 200,000 soldiers — and the 100 hectares surrounding the ridge were given to Canada by a grateful France in 1922 so that the monument could be built.

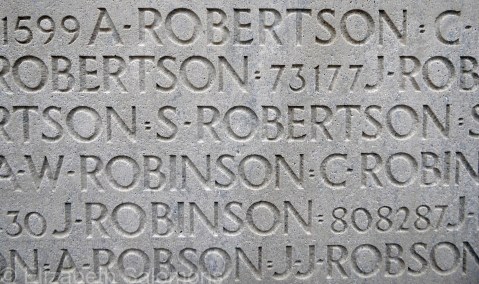

On the Vimy Monument are carved the names of 11,285 Canadian soldiers who died in France, but have no known grave.

Because many of the soldiers’ bodies at Vimy were never recovered (it was and still is too dangerous to walk over No Man’s Land because of the unexploded ordnance), the entire memorial site is considered a cemetery.

Here’s a surprising number: 25. That’s the number of metres between the Canadian and German lines — about the width of a NHL hockey rink. You can see for yourself how short that distance is when you stand in one of the reconstructed trenches.

The guides who take you into the underground tunnels at the Canadian National Vimy Memorial are all Canadian university students. Those tunnels served two purposes: they protected the Canadian soldiers as they moved ever closer to the German lines, and they allowed the soldiers to plant the underground mines that were set off just before the battle began.

Not all of the mines exploded, which is why there is so much unexploded ordnance. The grass is kept short by grazing sheep that are too lightweight to set off the mines.

It is believed there are 10 miles of tunnels at Vimy, dug by miners who had the necessary experience in tunneling underground. Although you can’t go into the tunnels without a guide, you are free to wander about the rest of the memorial site as you will.

The Vimy Monument itself is striking. Designed by Canadian sculptor Walter Seymour Allward, it took 11 years to build and was dedicated in 1936. Allward said the image of the twin pylons, which represent Canada and France, came to him in a dream.

On the monument itself are 20 allegorical sculptures so poignant and moving that I’m going to let the pictures speak for themselves.

And here is one final number: 2.

That’s the number of hours it takes to get from Paris to the Canadian National Vimy Memorial by car (about the same by train and taxi).

As to the value of a visit to Vimy Ridge, I have no more numbers.

That is immeasurable.

The Gardens of Schloss Schwetzingen

Remember Karl Theodor? The fellow I kept bumping into in Heidelberg? Turns out he had a summer home. (And was quarrying stone from Heidelberg Castle to build it. Tsk, tsk.)

That home would be this one, Schloss Schwetzingen or Schwetzingen Castle.

Karl Theodor spent a great deal of effort and expense on designing some rather splendid gardens behind the castle.

Which is what my friends and I came to see. There are several of them, all exquisitely landscaped.

There were also lots of ponds, along with the requisite ducks and geese.

More than 100 sculptures.

A few “follies,” as they call them in formal gardens, such as this mosque.

And a temple to Apollo.

There were so many gardens, in fact, that we didn’t even get to them all.

Oh, and guess what? Just outside the castle is Karl Theodor himself. I think this likeness has something to do with the fact that he fathered seven illegitimate children by three different women.

Who says Germans don’t have a sense of humour?

Heidelberg

After our lunch stop in Aachen, my German friends and I continued our journey to the south of Germany.

Here’s a question: What happens when you put a Canadian in the passenger seat of a German-made car driven by a car-mad German down the German Autobahn?

And here’s the answer: She giggles hysterically when it hits her how impossibly fast 214 km/h is after sneaking a glance at the speedometer.

Happily, the hysteria lasted only for a moment. And even at those speeds, it still took us much longer than I expected to reach our destination just outside of Heidelberg. (Remember, I’m the Canadian who thinks all European countries are tiny.)

Which meant we arrived after dark. But that made the end of the journey the most magical part of the day. After turning off the Autobahn, we drove through the countryside on what in Canada we call secondary roads. Suddenly, we were driving through the centre of Heidelberg. I’d been to Heidelberg before and knew, even in the darkness, roughly where we were. I looked up.

Yup, there it was. High above us, illuminated with floodlights, was the Heidelberg Schloss, or Heidelberg Castle.

It was quite the view on my first night in Germany.

Heidelberg straddles the Neckar River. From the hillsides on either side of the river valley, you have a pretty awesome view of the city. This is the view of the Old Town from the Philosophenweg, or Philosopher’s Walk. That’s the Castle behind the Old Town, up the hill a ways.

Here is the view of the Old Town from the Castle.

And here’s a better look at the Castle from the Castle Terrace.

The Castle is built out of Neckar Valley sandstone. The first structure on the site went up around 1300, and the prince-electors began to use it as a palace about a hundred years later. They added more buildings, all facing an inner courtyard and all representing different time periods and different styles of architecture from Renaissance to Rococo.

This wall is all that remains of the Renaissance Palace.

The castle was destroyed and rebuilt several times during the Thirty Years’ War (1618–48), and then completely destroyed by lightning in 1764, after which it lay in ruins for many years. People began hauling away its stone to build their houses, a custom that was stopped in 1800 by a Frenchman named Count Charles de Graimberg, who began restoring and preserving the castle.

Here’s a closer look at the bridge that crosses the Neckar.

It’s known simply as the Alte Brücke or Old Bridge, but its official name is Karl-Theodor Brücke after the fellow who arranged to have it built (this version, that is, which went up in 1788). Karl Theodor was a prince-elector. (Fun fact: The Holy Roman Emperor was not a hereditary title, but an elected one, and he was elected to that office by the prince-electors. The things I learn doing research for this blog.)

It seemed like every time I turned around in Heidelberg, I bumped into Karl Theodor. Not literally, of course, but figuratively as his likeness is everywhere. Here he is on the bridge he had built.

This is the view of the Bridge Gate from the bridge. The gate dates back to the Middle Ages, making it much older than the bridge itself, except for its Baroque spires, which were added in 1788.

The Old Town of Heidelberg is a lovely place to wander through. Its buildings are mostly in the Baroque style.

This house was built in 1592 in the Late Renaissance style, and is now a hotel.

Heidelberg is very much a college town. Heidelberg University is Germany’s oldest (founded in 1386) and most prestigious. A quarter of the city’s population are students. A fun place to visit is the Studentenkarzer or Student Prison, which was in use until 1914. Students were detained for unseemly conduct like public drunkenness (or what we call a typical Saturday night on campus), but were allowed out to go to class. While locked up, they took out their pens. Here’s some of their graffiti.

Heidelberg is one of Germany’s most visited cities and I’m not surprised. This was my third visit and I keep going back as it’s quite lovely.

On the flip side, Germany is the top source of tourists to BC from continental Europe by quite a margin. This too does not surprise me — I keep bumping into them in our parks. I think they like our mountains.

But what surprised me as my friends and I flew down the Autobahn is how much forest cover there is in the country. The Autobahn is bordered on either side by woodland. Heidelberg is surrounded by timbered hilltops. My friend’s house backs onto a forest.

And here’s another fun fact I learned while doing research for this post: the Brothers Grimm lived not far from Heidelberg.

Romantic castles and enchanted forests indeed.

Aachen

It had to happen. Eventually. Inevitably.

The day finally came when it was time for me to leave Amsterdam.

Happily, I had two friends to distract me. They came from Germany for a quick visit and that meant my last day in Amsterdam was more party-like than funereal.

And then, they drove me to their home in southern Germany. But to break up what turned out to be a long day of driving (why is it we Canadians always underestimate how large European countries are?), we stopped off in Aachen to have lunch with a mutual friend.

Aachen (pronounced AH-ken, with a bit of throat clearing on the “ch”) is in a tiny little corner of Europe where three countries come together: Germany, Belgium, and the Netherlands. Our time there was short, but long enough for a lightning quick walking tour of the old town.

In that lightning quick walking tour, I learned that Charlemagne was rather fond of Aachen, and made the city the capital of his Holy Roman Empire. I also learned that Charlemagne built a chapel, which became part of his palace. The palace no longer exists, but the chapel is now part of the Aachen Cathedral. It’s a pretty spectacular church — so spectacular that I’m going to save those photos for a post all their own.

This photo, though. I’m posting this photo because the architecture caught my eye. Only a few miles from the Dutch–German border, but I know I’m not in Holland anymore.

The Wittenberg Door

So I learned something the last time I was in Berlin. My dad and I were trying to take the train to Wittenberg, but almost ended up in Wittenburg.

Who knew one vowel could make such a difference? (And yes, this is why God made editors.) Wittenberg with an “e” is about 100 km southwest of Berlin. Wittenburg with a “u” is about 200 km northwest of Berlin.

In other words, we were headed in pretty much the opposite direction of where we wanted to be going.

After a quick chat with the train conductor, my dad and I disembarked at the next station, took a train to somewhere in the middle of nowhere, and waited there for yet another train that would take us south. We eventually did reach Wittenberg (with an “e”).

Why Wittenberg? Because we wanted to see this door.

That would be the door to the Schlosskirche or Castle Church to which Martin Luther is said to have nailed his 95 theses 500 years ago today, on October 31, 1517. You can see the tower of the Schlosskirche in the photo below.

Luther’s theses went viral, you could say, and caused a bit of an uproar in the Christian church. Wars ensued — lots of wars — and, well, a lot of general mayhem. The world has never been the same since.

Some might say a little reformation, now and then, is a healthy thing, but I doubt that Luther had any idea of what he was starting when he picked up that hammer.

Canada 150: Quebec City

At the start of my Canada 150 series, way back when, I said that a cross-Canada train trip should be on the Travel Bucket List of every Canadian. I myself haven’t quite completed that, but I came pretty close when I took the train from Vancouver to Quebec City.

It took me four days to cross five provinces. I was a student, so I had more time than money and back in those days taking the train was cheaper than flying. But still, it was the cheap seats for me, which meant I did not have a sleeping berth at night. When I finally disembarked, the conductor joked that I was starting to look like part of the furniture.

But travelling slowly across three-quarters of the country was so worth it. It gives you a sense of the scale of our country, and an appreciation for the regional differences.

Another way to appreciate regional differences is to spend a good chunk of time in other parts of the country. I travelled to Quebec City that summer to study French. The French didn’t much stick, but my perception of Quebec was changed forever.

It was the 1980s, the height of the Quebec sovereignty movement and the middle of a decade of constitutional conferences and accords that were the aftermath of the federal government repatriating Canada’s Constitution without Quebec. Yes, that’s a mouthful and I won’t get into explaining it here because if you’re old enough, you lived through it, and if you’re too young to remember, there are books you can read. But I mention it to explain the context for my summer.

My goal that summer, besides learning French, was to get to know the province of Quebec, so to speak. As a history major, I knew all about Canada’s two solitudes, but history doesn’t really, truly come alive until you walk its streets. And here’s what I learned: the difference between Quebec and the rest of Canada isn’t just its language, but also its culture and its history.

Language is obvious, of course. But it’s because of that language difference that Quebec has its own music scene, its own TV and film stars, and its own literature. I read a lot, but I can’t remember the last time I picked up a novel by a Québécois author. I think we English-speaking Canadians could do a lot better in appreciating and acknowledging Quebec culture.

And then there’s the history. What I most remember about that summer is realizing exactly what je me souviens means to Quebeckers. Its literal translation is “I remember” and it is the province’s motto. It’s said to refer to how Quebeckers will always remember their culture, their traditions, and their history. But when I saw one of those sound and light shows for tourists of a model-sized re-enactment of the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, the penny dropped for me. Je me souviens means “I remember 1759.”

The Battle of the Plains of Abraham took place on September 13, 1759. The British soldiers, led by General James Wolfe, climbed up the cliffs from the Saint Lawrence River to the Plains of Abraham at Quebec City, taking the French troops, led by the Marquis de Montcalm, completely by surprise. It was all over within an hour. The French loss marked the turning point of the Seven Years’ War. France gave up control of its colony in New France, but was allowed to keep two small islands off the coast of Newfoundland (Saint Pierre and Miquelon) and its holdings in the West Indies (the islands of Guadeloupe and Martinique).

Keep in mind that New France at that time consisted of present-day Labrador, Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, and what is now the American Mid-West from the Great Lakes south to Louisiana. It was a far larger land mass than Britain’s Thirteen Colonies. Some historians like to draw a straight line between France losing New France and the American Revolution a few years later.

I’m getting lost in the history here, I know. But the point I want to make is this: if Montcalm had not lost the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, if France had not ceded its holdings in New France to the British, if the American Revolution had not been fought, if the Loyalists had not moved north into Canada, there is a pretty good chance that Canada would be a French-speaking nation. So when someone in Quebec says “je me souviens,” they are remembering all that.

I put all these thoughts into a short essay I read aloud to my French class on our last day of classes that summer. We met on the Plains of Abraham, of all places, for a class picnic and after I finished reading my essay, my teacher said to me, “Tu pense comme une Québécoise.”

You think like a Quebecker.

I don’t know about that, but I do know that my summer in Quebec City gave me a better understanding of how Quebeckers see their place in Canada.

I don’t have a photo of the Plains of Abraham, but here’s one of Notre-Dame-des-Victoires, a small church in the Lower Town of Quebec City. It is less than two kilometres from the Plains of Abraham and was almost completely destroyed by the British bombardment that preceded the battle in 1759.

Canada 150: Montreal

I wasn’t going to include Montreal in my Canada 150 series. Truth is, I haven’t spent a lot of time there and I don’t know the city well at all. But as I was thinking about my infrequent visits, it suddenly dawned on me. The last time I was in Montreal was on a May long weekend, and the city was deep into its 350th birthday celebrations. And this year, on May 17, Montreal celebrated its 375th birthday.

Gulp. It’s been 25 years since I’ve visited the home of my first love. (That would be the Montreal Canadiens.)

This photo is of the Marché Bonsecours (Bonsecours Market). Opened in 1847, it was the main public market of Montreal for more than a century. Today it houses restaurants and shops and a reception hall.

Kampen

I started off my summer in Amsterdam by hanging out with my nieces for a couple of weeks. If you are ever jaded about travel (and I’m not, but, I dunno, some of you might be … ), go travelling with a couple of teenagers. It lets you look at a foreign country with fresh eyes. I felt privileged to be able to introduce those two to Europe and I am pretty sure they went home with the travel bug firmly planted.

My own travel bug was also firmly planted on a trip to Europe while a teenager. Coincidentally, I ended my summer in Amsterdam with a day trip to where it all began.

That would be Kampen.

Kampen is a small city in the province of Overijssel, about 90 minutes from Amsterdam by train. Overijssel means “over the IJssel” — the IJssel being the river that runs beside Kampen. Because of that river, and its proximity to the Zuiderzee, Kampen became an important trading town and it joined the Hanseatic League (a loose union of towns that controlled the maritime trade of Northern Europe during the Middle Ages).

Which means Kampen is just one more well-preserved medieval Dutch town.

Which means Kampen is just one more well-preserved medieval Dutch town.

Well, not exactly. Kampen is more than that. It’s where I first learned how to live in a foreign country.

Kampen is not quite as pretty as Leiden or Delft — it doesn’t have as many cute canals and bridges that those other cities have. What it does have are three poorten, which is Dutch for “gates.” They are what’s left of the city’s walls.

Kampen also has a bunch of churches. The Bovenkerk stands out because of its height (boven means “above”) and it makes for a pretty picture from across the IJssel River. Below is the view you have when you arrive in Kampen by train.

Once you cross the IJssel, you are immediately immersed in the historic centre of Kampen. This is the stadhuis or town hall.

And this is Oudestraat (Old Street), the main shopping street. When we lived in Kampen, cars and delivery trucks were still allowed to drive up and down Oudestraat. Total chaos, it was.

The tower at the end of Oudestraat is the Nieuwe Toren (New Tower). If you look closely, you see a cow hanging from the tower. (Not real, I assure you.) The story goes that the fine people of Kampen wanted to get rid of the grass growing on the roof of the tower. Someone had the bright idea of putting a cow up there (to eat the grass), but she died on the way up. They hang a replica every summer to remind themselves of how clever they were.

And yes, that is probably the weirdest story I can tell you about any place I have ever lived.

About those city gates. Facing the IJssel River is the Koornmaarktpoort. It is the oldest of the three gates.

This is the Cellebroederspoort.

And this is the Broederspoort.

Here it is from the other side.

On the one side of the Cellebroederspoort and the Broederspoort is a rather large and lush park, full of geese and ducks and rather large trees. I have always thought that the Netherlands made such an impression on my first visit not so much because it was a foreign country (though there was that, too), but because I had grown up on the North American prairies where large, leafy trees are few and far between.

We kids spent a lot of time in that park, if I am remembering correctly. Our mornings were spent studying, our books spread across the dining room table with the French doors wide open to the garden behind the house. But in the afternoons, we were free. We had our bikes and we had that park and we had an entire town to explore. We also went to the weekly market with our mother, and on drives through the Dutch countryside with both of our parents.

I am sure my memories are romanticizing the experience. I do remember feeling homesick for Canada, and I am sure we drove our mother around the bend, not going off to school every morning. But even so, I feel blessed that our family had that time together.

There is a lot to be said for visiting the European capitals when you go to that continent for the first time — and I’m so glad my nieces had their chance this summer. But I also know they found the traffic and the people (and the bikes!!) a little overwhelming. And so, there is also a lot to be said for exploring a small, Dutch medieval town on your own when you’re just a kid, as an introduction to Europe.

On your own on a bike.

Amsterdam’s Canal Houses

And then there are the canal houses.

Google “unique European architecture” and Amsterdam is sure to be on the list. That’s because of its unique canal houses.

Amsterdam’s canal houses are narrow, they are tall, and they are deep. Although the place where I stayed in Amsterdam is a modern house by Dutch standards (a mere 125 years old) and doesn’t face a canal, it too was built in the Dutch canal house style. And let me tell you: you don’t appreciate how narrow, tall, and deep these houses are until you’ve climbed a narrow, vertigo-inducing staircase all the way up to the fifth floor.

A typical canal house is only six metres wide. The reason why they are so narrow? It’s because canal houses were taxed on their width. The city governors needed money to pay for the massive canal expansion of the seventeenth century (when most of the canal houses were built), and knew they could raise the money by taxing the most desirable properties, which the canal houses were.

The Dutch are notoriously thrifty, shall we say, and anything they can do to save a cent, they will do. So they built narrow houses.

Many canal houses were multi-functional: they served as both family home and warehouse for the merchants who lived in them. The first storey was where the company’s office was located (at front) and where the family lived (at back). The upper storeys were the warehouse. At the top of each house was a beam with a hook. When the merchant needed to haul his trade goods into the warehouse, he attached a pulley and rope to the hook. Those same hooks are still used today when moving furniture or during renovations when building materials need to be brought into a house.

Amsterdam’s canal houses are still in use as family homes, but also as restaurants, hotels, museums, and offices. I lost count of how many times I walked past a canal house, its doors open wide to the street so I could look right in on an open-concept office, with rows of white computer-laden tables or groups of people gathered around a long meeting table. The offices all looked like remarkably relaxed work environments.

Although the canal houses follow a pretty similar cookie-cutter style from one to the next, where they do differ is in the style of their gables.

There’s the step gable.

And there is the spout gable. It looks like an inverted funnel, and indicated that the canal house was a warehouse rather than a residence.

The neck gables allowed for the most individualization. The corners created by the 90-degree angle of the facade were filled in with ornate decoration that reflected the Baroque style of the time.

Sometimes the neck gables were built in identical pairs.

But often you see a row of canal houses with each gable different from the next. In this photo, from left to right, is a neck gable, a spout gable, and a bell gable. The bell gables are called that because the shape of the top of the gable resembles a church bell.

Here is a row of mostly bell gables. Note how the houses are tilted. Amsterdam’s canal houses are built on top of wooden piles that were pounded into the swampy peat bog until solid sand was reached. But as the land shifts through the centuries, so too do the houses. This particular row is known as the Dancing Houses.

Here’s another thing I learned last summer. Marvelling at the Amsterdam canal houses is a whole lot more fun when you have a house builder along with you. My brother would shake his head, chuckle, and say, “There are no straight lines.” I don’t know if he was unsettled by the lack of straight lines, or merely fascinated, but after he left, for the rest of the summer, I walked around the city looking for straight lines.

I didn’t find many.